Mideast countries feel pinch of soaring food prices during Ramadan. The ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict, which came at a time when economies worldwide are still grappling with the adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, also poses a challenge to regional food security

Rising food prices and a worsening economic situation have forced many Middle Eastern families to limit their Ramadan budgets, resulting in lower meat purchases and other traditionally popular food.

During the holy fasting month of Ramadan, Muslims usually make various kinds of food for the fast-breaking meal, known as Iftar. This year, with the Russia-Ukraine conflict compounding the economic difficulties caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, there are fewer choices for many families in the Middle East.

Rana Itani, a 34-year-old divorced resident of Beirut, said she could no longer afford the food that her two kids are fond of due to Lebanon’s ongoing economic woes.

“My parents provide me with food now. They either send it to me or my kids, and I go to their place,” Itani, who works as a secretary at a private company in the Lebanese capital, told Xinhua.

Itani, who has been working for the company in Beirut’s Hamra neighborhood for 12 years, is paid 3.5 million LBP (2,308 U.S. dollars) monthly. She also gets 1.5 million LBP from her ex-husband for their children’s school tuition.

“The money I earn is barely enough to cover living, education and health costs … I pay 2 million LBP for the house rental and 1.6 million LBP for power generator fees.” Itani sometimes receives financial help from relatives yet remains short of cash due to the skyrocketing prices of commodities.

“Prices have gone up tremendously … I cannot buy vegetables or fruits. This Ramadan is different,” Itani said, adding that she has been trying to find an extra job to earn more money.

Lebanon has been facing an unprecedented financial crisis amid a shortage of foreign currency reserves, exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic and the Beirut port explosions in 2020 that destroyed a big part of the capital city.

In 2021, the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Western Asia said that the poverty rate in Lebanon was up to 74 percent, while the UN Children’s Fund reported that 77 percent of households did not have enough money to buy food.

The ongoing Russia-Ukraine conflict, which came at a time when economies worldwide are still grappling with the adverse effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, also poses a challenge to regional food security.

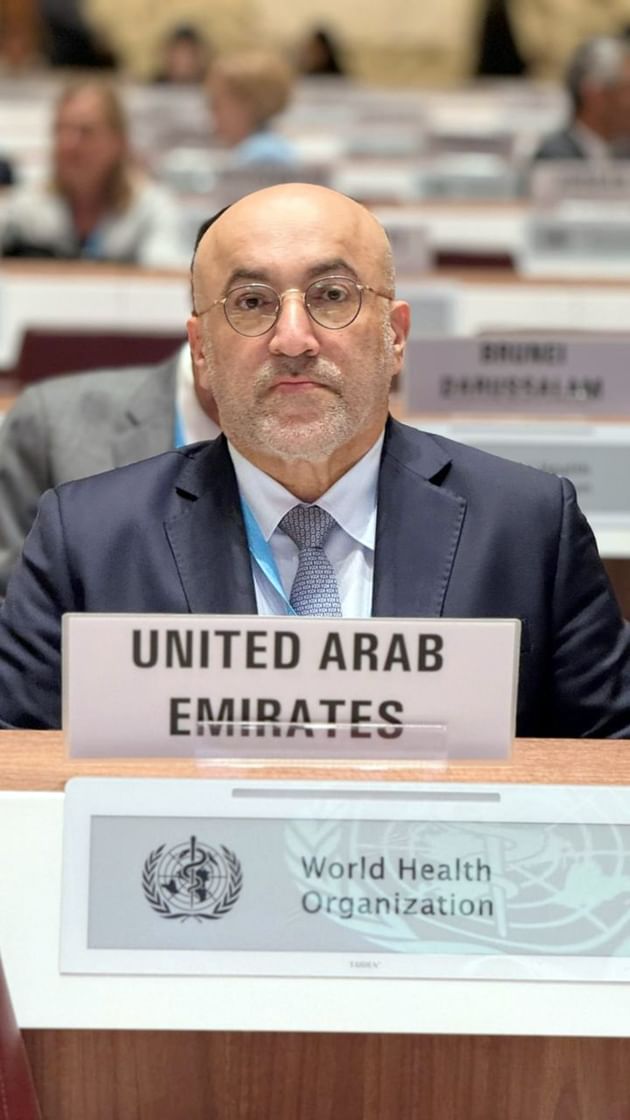

“Many countries rely on supplies from Ukraine and Russia for their food import needs, including numerous least developed countries and low-income food-deficit countries,” Boubaker Ben-Belhassen, director of the trade and markets division of the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), told Xinhua in a recent interview.

Disruptions to Ukrainian and Russian grain and oilseed production and exports and restrictions on Russia’s exports can significantly impact global food security, noted Ben-Belhassen.

“FAO’s simulations suggest that international food and feed prices could rise by 8-22 percent above the baseline levels, and the number of undernourished people could increase by 8-13 million people in 2022/23,” he said.

For several weeks, markets in the Gaza Strip have witnessed a remarkable increase in staple food prices, mainly poultry, with the cost of chicken reaching 5.5 U.S. dollars for the first time in years. The item cost 1.5 dollars per kg at most before Ramadan, according to residents.

Soaring prices have made it difficult for many Palestinians to make the meals they prefer during Ramadan.

Sohaila Abdel-Hady, a mother of seven from Deir al-Balah in central Gaza, can’t afford to cook chicken for her family. She chose frozen bovine meat imported from Israel as a cheaper alternative.

In the Egyptian capital Cairo, the family of Mahmoud Ahmed, a 40-year-old security guard at a residential building, has not eaten meat for almost one month.

“We are used to cooking meat, rice and other dishes on the first day of Ramadan, but we have not eaten meat since the beginning of the holy month,” the father of four told Xinhua, complaining of rising prices.

“This Ramadan is not as happy as the previous ones because of lack of money and the surging prices of all goods,” said Ahmed, whose monthly salary is around 200 dollars. “My children want to eat meat and chicken … I can buy 1 or 2 kg of frozen meat for the whole month.”

To soothe the markets, governments in the region have enacted policies to encounter soaring prices for necessities, including diversifying food imports, increasing food subsidies and lowering food taxes. Some countries have shored up their food stocks and reduced reliance on food imports.

In Egypt, the world’s largest wheat importer, the market price of a ton of flour increased to 11,000 Egyptian pounds (600 dollars) in March, up from 9,000 pounds a month earlier, according to official data.

“A conflict usually impacts the global economy and causes a surge in the price of most commodities, but it mainly affects those countries that import most of their goods,” Abu Nakr al-Deeb, an Egyptian economist, told Xinhua.

He noted that most Middle East countries rely heavily on Russia and Ukraine for food imports, mainly grains, adding that prices will not rapidly return to normal even after the conflict ends.

Al-Deeb said the conflict has raised fuel prices such as gas, oil and coal, posing a great challenge for non-energy-producing countries.

ALSO READ: RAMADAN BUZZ AT TURKISH BAZAARS

“This conflict plunged many countries of the region into a state of stagnation and affected the exchange rate of local currencies against foreign currencies, especially the U.S. dollar,” he said.

The expert said governments in the region have taken a series of measures to maintain the flow of supplies and control the prices of commodities, mainly food.

In Egypt, which imported 80 percent of its wheat from Russia and Ukraine in 2021, the central bank decided to raise the key interest rate by 1 percent for the first time since 2017.

For three months, the Egyptian government has also set a fixed price for unsubsidized bread to ensure food security for those who mainly depend on the staple, al-Deeb noted.

“Such measures can ease the burden,” al-Deeb said, “but still, the crisis is ongoing.”