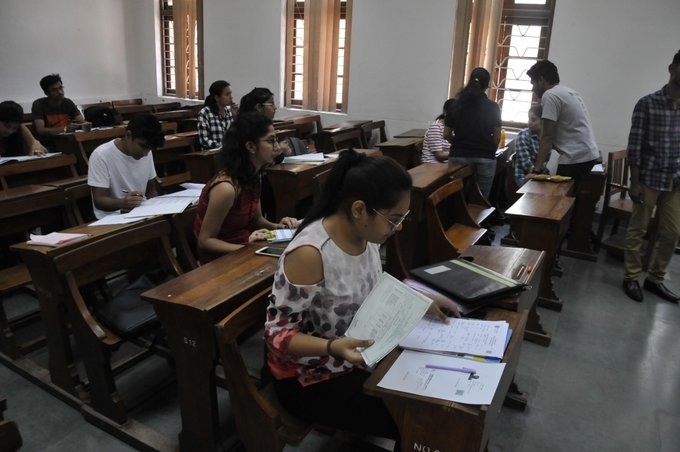

Thousands of young Indians are finding themselves graduating with limited or no skills, undercutting the economy at a pivotal moment of growth.

More than 5 million Indians enter the 15-to-24 age group every year, adding a demographic thrust to the demand for more colleges and universities. Properly educated and employed, these young people could bring the country a demographic dividend, the sort of surge in growth that buoyed many of the Asian “tiger” economies from the 1960s to the 1990s. But if India does not create high-quality colleges for its youths, it risks reaping a demographic disaster.

The higher education commission recently released a list of 21 “fake universities,” many of them no more than a mailing address or signboard hanging over a shop, temple or hole-in-the-wall office space. A government regulator that focuses on technical schools named 340 private institutions across India that run courses without its accreditation. Of more than 31,000 higher education institutions, only 4,532 universities and colleges are accredited.

Meanwhile, business is booming in India’s $117 billion education industry and new colleges are popping up at breakneck speed. Yet thousands of young Indians are finding themselves graduating with limited or no skills, undercutting the economy at a pivotal moment of growth.

Desperate to get ahead, some of these young people are paying for two or three degrees in the hopes of finally landing a job. They are drawn to colleges popping up inside small apartment buildings or inside shops in marketplaces. Highways are lined with billboards for institutions promising job placements.

India has the world’s largest population by some estimates, and the government regularly highlights the benefits of having more young people than any other country. Yet half of all graduates in India are unemployable in the future due to problems in the education system, according to a study by talent assessment firm Wheebox.

Many businesses say they struggle to hire because of the mixed quality of education. That’s kept unemployment stubbornly high at more than 7% even though India is the world’s fastest growing major economy, reported Bloomberg.

The complexities of the country’s education boom are on show in Tier II cities. Massive billboards with private colleges promising young people degrees and jobs are ubiquitous.

Higher degrees, once accessible only to the wealthy, have a special cachet in India for young people from middle and low-income families.

In 2019, the Supreme Court barred the Bhopal-based RKDF Medical College Hospital and Research Centre from admitting new students for two years for allegedly using fake patients to meet medical college requirements. The college initially argued in court that the patients were genuine, but later submitted an apology after an investigative panel found that the purported patients weren’t really sick, reported Bloomberg.

The medical school is part of RKDF Group which has wide network of colleges in areas from engineering to medicine and management. The group faced another controversy last year. In May last year, police in Hyderabad arrested the vice chancellor of RKDF Group’s Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan University as well as his predecessor for alleged involvement in giving out fake degrees. Still, students could be seen flooding into several of RKDF’s institutions in Bhopal. One branch had posters of their “Shining Stars” – students who were placed in jobs after graduating.

India’s education industry is projected to hit $225 billion by 2025 from $117 billion in 2020, according to the India Brand Equity Foundation, a government trust. That’s still much smaller than the US education industry, where spending is estimated to be well above $1 trillion. In India, public spending on education has been stagnant at about 2.9% of GDP, much lower than the 6% target set in the government’s new education policy.

India has regulatory bodies and professional councils to regulate its educational institutions. While the government has announced plans to have a single agency that will replace all existing regulators, that’s still at the planning stage. The education department didn’t respond to a request for comment.

ALSO READ: Ireland grants highest number of work permits to Indians