Hasan, who currently lives in Bangalore maintains that her relationship to Delhi and history is that of an enthusiast, that the layers of history in the Capital and the crassness of the city make for an interesting combination that comes together in Alif who feels a “warm, intimate hatred” for the place he has never left and is likely to never leave…writes Sukant Deepak

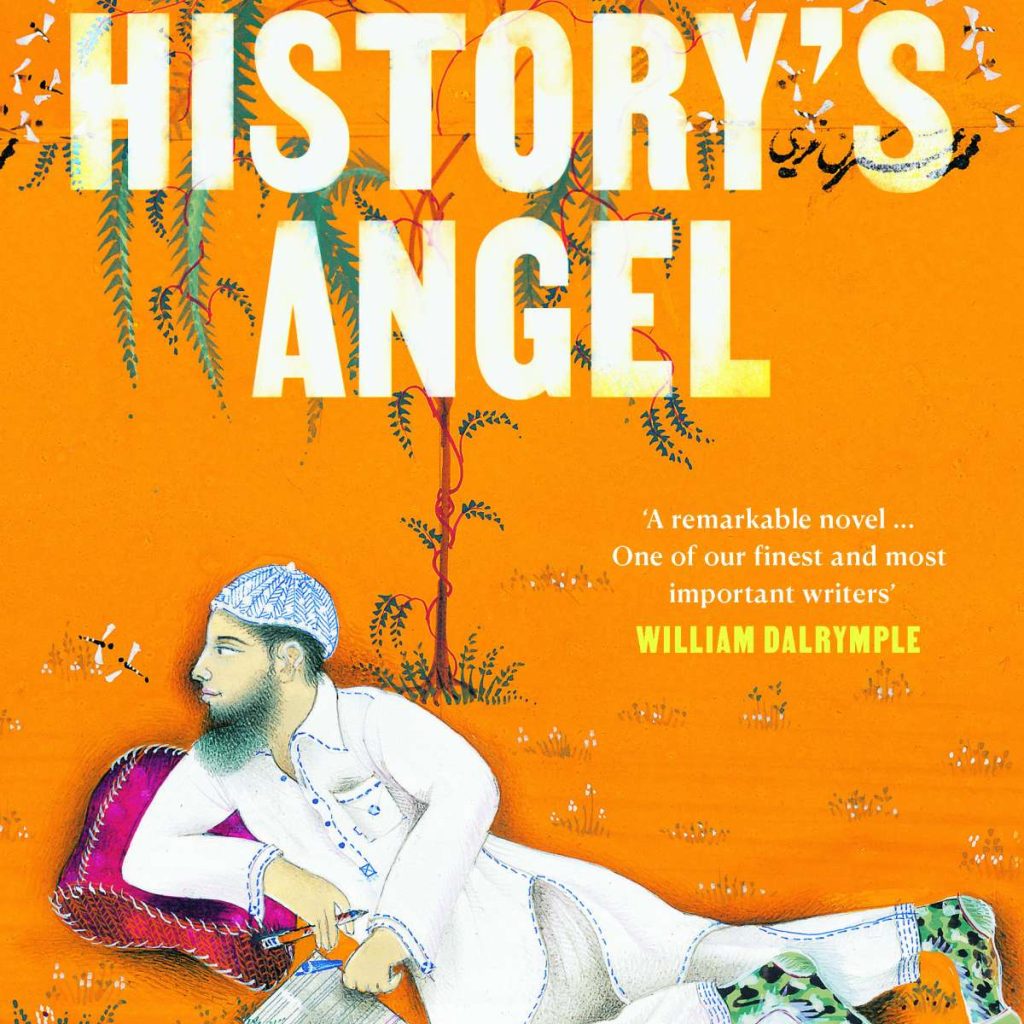

It may explore the varied social and political tensions engulfing contemporary India. At multiple levels, it forces the reader to encounter her/his own biases and barbarity, but surprisingly the same is executed with almost heartbreaking delicacy, of prose that punctuates, characters you want to shake up in this powerful biography of our times. The tenderness in author Anjum Hasan’s ‘History’s Angel’ (Bloomsbury Publishing) is in fact sometimes more ‘brutal’ than what is in the background, what is engulfing the characters under the ‘history’ they stand beneath.

But Hasan says it is important to remember that literature remains one of the last spaces where one can breathe, perhaps even smile, though novelists are not above getting shouty.

“I needed to create a character like Alif who is sympathetic and who can, however morosely and privately he does it, take the long view. As in the scene where a potential landlord is railing at him and his wife — he still wishes he could comfort the man for his sense of loss, his genuinely painful delusions about the great purity of the Indian past,” she tells.

The story revolves around Alif Mohammad, a middle-aged, mild-mannered history teacher, living in contemporary Delhi, at a time in India’s history when Muslims are seen as either hapless victims or live threats. Though his life’s passion is the history he teaches, the present is pressing down on him: his wife is set on a bigger house and a better car while trying to ace her MBA exams; his teenage son wants to quit school to get rich; his supercilious colleagues are suspicious of his perorations; and his old friend Ganesh has just reconnected with a childhood sweetheart with whom Alif was always rather enamored himself.

And then the unthinkable happens. While Alif is leading a school field trip, a student goads him and, in a fit of anger, Alif twists his ear. His job is suddenly on the line, and Alif finds his life rapidly descending into chaos. Meanwhile, his home city, too, darkens under the spreading shadow of violence.

Now that is the easy/convenient reading of Hasan’s latest work. But Hasan could also have been Amit/Sukhwinder.

“I’m delighted you think so. It is a vindication of the novel to see Alif as an every man, at least an Indian every man,” the author asserts.

Considering the protagonist is both a historian and someone caught in a difficult historical moment, she believed the play between those two things would be great material for a novel. It was also about exploring what innocence means — when we say regular folk is suffering or ordinary people have been brainwashed.

“I am not sure there is anything like absolute innocence in adults, at least not anyone with a modicum of education. What is the point of being educated if we let ourselves go down so easily? And so the novel is partly set in a school.”

Hasan, who currently lives in Bangalore maintains that her relationship to Delhi and history is that of an enthusiast, that the layers of history in the Capital and the crassness of the city make for an interesting combination that comes together in Alif who feels a “warm, intimate hatred” for the place he has never left and is likely to never leave.

“I was also curious what it might be like to live in and feel at home in the walled city yet shrink from the stereotypes about grand Muslim culture often associated with it,” she adds.

Alif does not really ‘act’ despite what happens to him constantly. One wonders if his inertia in fact his way of ‘acting’, and is he symbolic of the middle-class liberals?

“Yes, he is often ducking out or shuffling off, or keeping mum when we expect him to take a stand. Except, I would say, in that one critical scene when his father flies off the handle. Is this diffidence, even moral laziness, true of Indian middle-class liberals in general? Perhaps. When public life is humming along smoothly and everyone has their place in the sun, it seems fine to retreat into a life of the mind. But what if things are breaking down fast all around you? Is there a price to pay for doing nothing? Not sure, but I was trying to ask the question…”

Someone who is a novelist, short-story writer, poet, and editor, insists that all of them do not come together in one work, and with difficulty in one person.

Currently working on a non-fiction book on Shillong, the town she grew up in, the author, whose process is about trying to stick with writing every day adds, “In the next work, I have borrowed some things from fiction writing like character and plot, but essentially it is an attempt to write a past and present history of a fascinatingly, if unevenly and partially cosmopolitan city.”