Xi Jinping is fashioning his expansionism through the Japanese method of kaizen, writes Prof. Madhav Nalapat

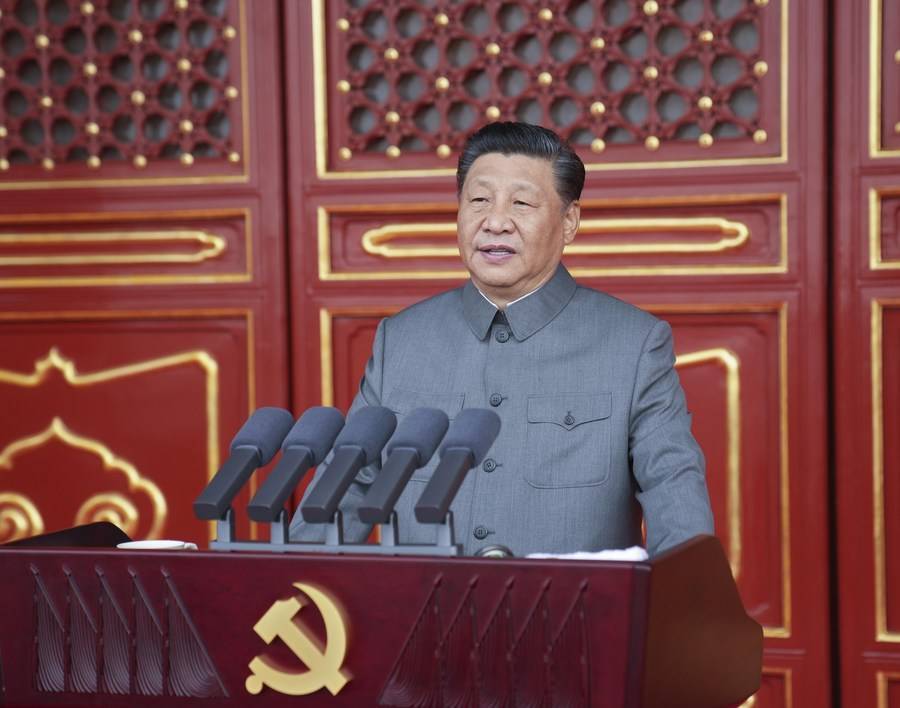

As much as what is being sought to be accomplished by him and the rest of the Communist Party of China (CCP), Xi Jinping is relying on the long-time propensity of the leaders of major democracies to make wrong strategic choices, and formulate erroneous policies. He expects such self-goals to push the PRC not just to the top of the table in GDP rankings, but to establish first primacy over the global geopolitical landscape. Xi Jinping Thought is a further development of Mao Zedong Thought, with the latter getting modified and adapted to meet the conditions believed within the CCP to be prevalent in the 21st century.

The core remains Han exceptionalism, presented as Chinese exceptionalism. It is no accident that the most sensitive slots within the PRC state security establishment in particular are filled with those who are from the Han majority of the population of the country. The others may be given impressive titles, in an effort at obscuring the reality of Han identity being at the core of the praxis of CCP doctrine, but their influence over policy and control over outcomes is scant.

There are numerous external commentators who speak confidently of the “resistance” and “inner party crisis” that is brewing within the CCP, and the possibility of such dissidents succeeding in displacing Xi, much the way the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU) deposed Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev in 1964, two years after the Cuban missile crisis, in which CPSU General Secretary Khrushchev failed to call President Kennedy’s bluff of launching an all-out war (including with nuclear weapons), were the USSR to station ballistic missiles in Cuba.

Aware of the pitfalls that may ensue to his own position at the apex of power in China should a military adventure fail, Xi is fashioning his expansionism through the Japanese method of kaizen, seeking to constantly improve the position of the PRC in a manner that would avoid an all-out conflict, especially with the US. Fortunately for him, the attention of the US and much of NATO seems fixated on Russia, just as was the situation during Cold War 1.0.

A conflict involving NATO and Russia in Europe would remove much of the pressure that has been building up against Beijing’s activities in the Indo-Pacific for the next decade, if not more, in an even greater way than the 9/11 attacks of 2001 made President George W. Bush veer away from focusing on the rising challenge posed by China to the Middle East and Afghanistan.

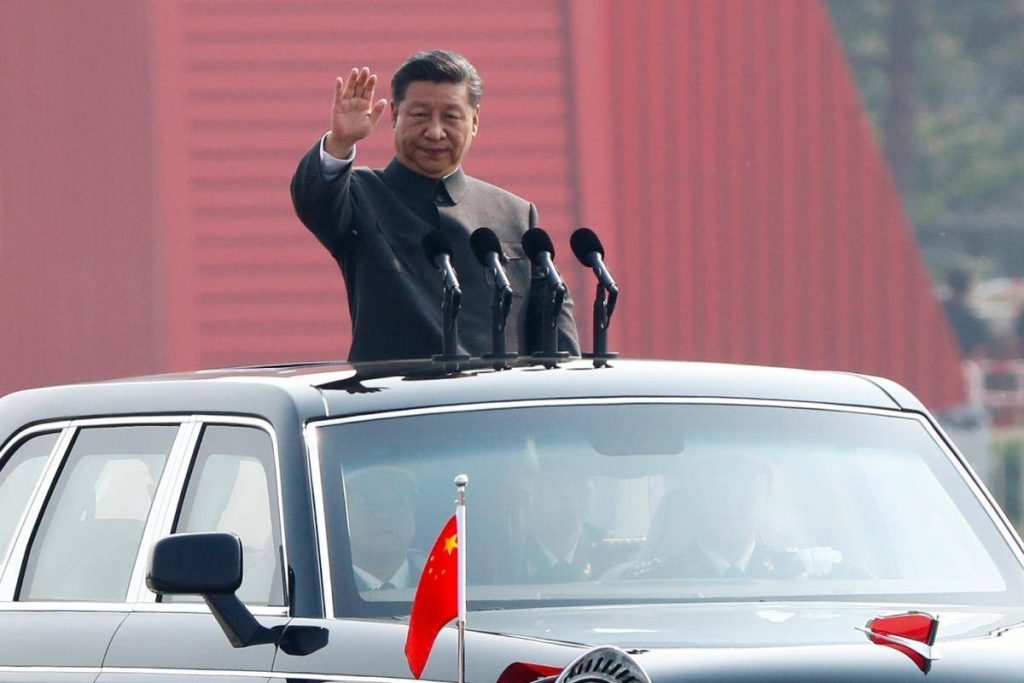

The CCP leadership made full use of that opportunity, and by the time Xi Jinping emerged as the ruler of the PRC in 2012, had leveraged policies sufficiently to make it the second superpower, just behind the US in influence and capabilities. By 2015, the term “CCP leadership” covered not the Standing Committee and leading elements in the CCP, but solely the Office of the General Secretary of the CCP. Today, through his security services and the harnessing of technology, Xi has accumulated more personal power than was the case even with Mao Zedong during his years in office as the Great Helmsman of the CCP.

Both Xi’s predecessors, Jiang Zeming and Hu Jintao, have clearly retreated into the shadows, perhaps awaiting better times. Within the Han population, Xi Jinping has become genuinely popular for his expansive promise of a future where they will run the globe much as those of European descent did in previous centuries. The General Secretary’s public cashiering and humiliating of princelings and billionaires has further boosted his appeal as a “man of the people”.

Those who believed from the days of the 2011 Arab Spring onwards that control over the streets would succeed in effecting if not regime change, then regime modification, at least in Hong Kong have been disappointed. Having performed its role of gateway to the world during the period of economic modernisation from the 1980s onwards, Hong Kong has lost much of its essentiality to the PRC, as evidenced by the manner in which the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region (HKSAR) has in effect become just another Chinese province.

More people in Shanghai speak English than in Hong Kong these days, and Beijing controls the HKSAR as completely as it does other parts of the PRC. Mass manifestations of public anger may yet erupt in the future, should there be a catastrophic decline in economic output or defeat in a kinetic conflict, but as yet, the conditions for that seem distant. Rather, there are other faultlines, which presently lurk under the radar, almost invisible, that may in future threaten the hold of CCP General Secretary Xi over the country. These relate firstly to matters of faith. Not just the experience of Russia and parts of East Europe but any catechism would make it clear that Christianity as a theology is antithetical to Communism, even that of the Mao-Xi variety.

However, unlike his predecessors Jiang and even more Hu Jintao, Xi appears to be opposed to any form of organised religion, including those that are diluted through the sieve of party control. Unlike in the past, when Buddhism was sought to be showcased as more Chinese than Indian, these days even that faith is facing leaner times. This is creating resentment within the minds of believers, although this mood is still dormant at present. Similarly, belief in democracy as an attractive way of life is percolating through the psyche of the Han people, fuelled by the success of Taiwan in both retaining democracy as well as a healthy economy, Taiwan’s success has come despite vigorous and often overt CCP efforts at undermining that country.

More than anything happening elsewhere, the Taiwan example has broadened a longing for democracy that is inconsistent with Xi Jinping Thought. The third faultline facing Xi’s project is factionalism. The severity of the consequences faced by those regarded as unreliable where adherence to the control of Xi over the party and the country is concerned has generated not just fear, but in many a sullen albeit silent mood that is waiting for conditions that would facilitate a largescale eruption of discontent. Much the way those opposed to hyper-authoritarian governments in the past became willing to act as the agents of external forces, there may be a flow of what at the moment is just a trickle of defections from the PRC or within that country, from General Secretary’s project of a China Dream with Xi Characteristics. For Xi, it is All or Nothing, and it will not be long before the shape of the eventual outcome emerges.