If nothing else, we learned to tolerate, if, not exactly respect, religious and cultural differences. Despite tensions, we got along. We managed to be civil to each other…reports Vishnu Makhijani

The foundations of a secular India were laid against the background of mutual suspicions between the Hindu Right and the Muslim leaders in the run-up to Indias Independence, “not exactly propitious circumstances for experimenting with an alien concept that had proved controversial even in the lands of its birth”, says a new book on the disruptive issue that urges a new beginning with “less contentious alternatives” that will enable the two communities to live in peace and harmony.

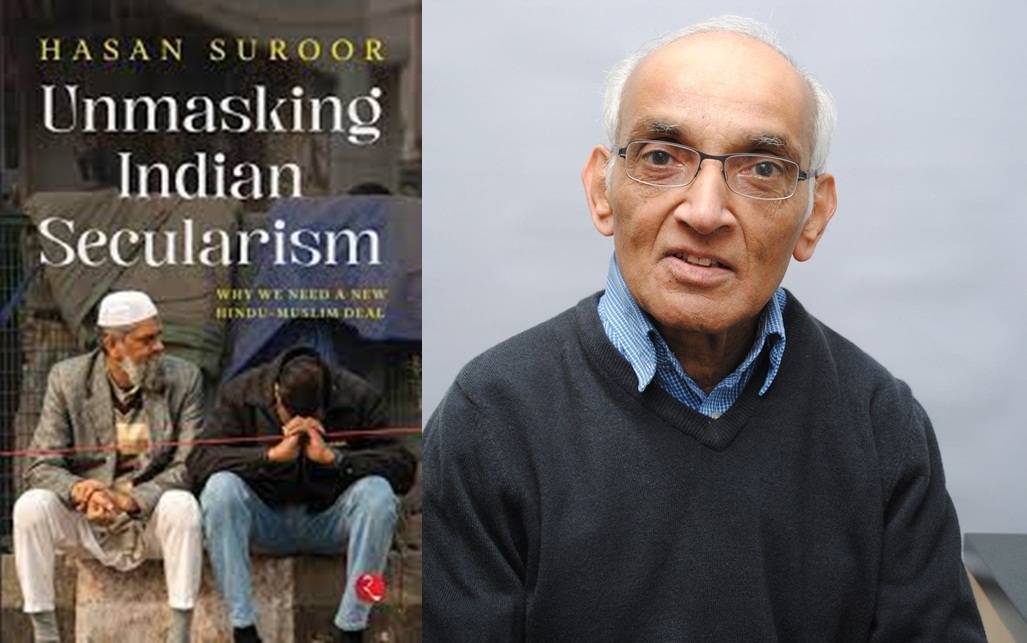

“Looking back, in the light of subsequent events, it is easy to question that decision. To be sure, it was a deliberate choice driven by Jawaharlal Nehru’s westernised liberal outlook. There was no attempt to explore an indigenous model: a system that would have recognised the predominantly Hindu nature of Indian society without necessarily declaring India a Hindu state,” journalist-author Hasan Suroor writes in “Unmasking Indian Secularism – Why We Need A New Hindu-Muslim Deal” (Rupa).

“The efficacy of the secularism project is debatable, but the problem is that much of the debate has become too politicized to allow an objective evaluation. And it is not a recent change; it has been so for as long as I remember. Most of the discussion has been shaped by ideological and party lines reducing it to a Liberal versus Right and, worse, Hindu versus Muslim issue,” Suroor writes.

This has resulted in a situation where “advocates of secularism hail it as the only show in sight and are not willing even to consider any other alternative, its opponents find no advantage to it, rubbishing it as a western import and a liberal conspiracy against Hindus”, he adds.

At the same time, the author admits that “for all its flaws and bungled execution”, secularism served its purpose at a time when the country was reeling from the aftermath of a communal bloodbath in the wake of Partition.

“If nothing else, we learned to tolerate, if, not exactly respect, religious and cultural differences. Despite tensions, we got along. We managed to be civil to each other.

“But the problem with sticking plasters, even the best of them, is that they are just that: sticking plasters can do only so much to alleviate a situation. They are not a substitute for a permanent fix. That is what happened with secularism,” Suroor writes.

It started to wear out “in the absence of any serious effort or a coherent strategy to fix the deepening communal divide stoked by groups opposed to the idea that Muslims should enjoy equal status in Hindu-majority India. Its abuse by secular parties through unprincipled compromises with Muslim fundamentalists groups in the name of protecting Muslim ‘identity’ compounded the crisis. This led even moderate/secular Hindus to start questioning secularism, suggesting that it was simply a cover to appease Muslim voters”, the author writes.

“The truth is that, like it or not, and regardless of the reasons, there is now a ‘new’ majoritarian India, and a refusal to acknowledge it will not make it go away. Not to put too fine a point on it, a Hindu India is already here in all but name,” Suroor maintains.

“We might not be able to ‘unbecome what we have become’…but we can try and limit further damage. And that means a willingness to start looking for less contentious alternatives based around what binds us by virtue of common citizenship and shared history rather than what divides us. I believe that a common national culture can be the basis for a new Hindu-Muslim settlement placing cultural affinity above faith,” he adds.

What is preferable, the author asks.

“A secular state on paper, but in effect practicing religious apartheid, or a state with an official religion but secular in practice, a sort of secular Hindu state, for example?”

Politically isolated and facing an existential crisis, “the question before the Muslim community is whether it wants to prolong the agony and suffer daily humiliation or try and find a dignified way out of it. There are no easy options: either we continue to be trapped in a no-man’s land, nominally secular, but in practice discriminatory, waiting for Godot to deliver us from our misery; our swallow our ego, grind our teeth and give up the tottering ghost of secularism for good. It might seem like an extreme step but in effect, we will be simply formalising what’s already a de-factor situation”, Suroor writes.

Some will see this as “surrender” but will actually allow “us to bow out at a time of our own choosing rather than have a solution imposed on us, as happened in the case of Babri Masjid and triple talaq. In exchange, we can insist on constitutional and legal guarantees around the protection of Muslim rights as equal citizens of India”, the author maintans.

“Let’s get this straight: there’s no Godot coming to our rescue. Secularism and Muslims are considered lost causes and increasingly a political liability even by avowedly liberal mainstream parties. They’re vying with each other to demonstrate their Hinduness, a sign that the Indian political landscape has changed for good. There’s a new normal…which, in this case, means that we stop endlessly arguing about the past and, instead, move on. And try to make the best of a bad situation.

“”It’s easy to bury one’s head in the sand and refuse to acknowledge the reality, but it requires courage to confront it and deal with it,” Suroor contends.

ALSO READ-Steve Lauds Secular India