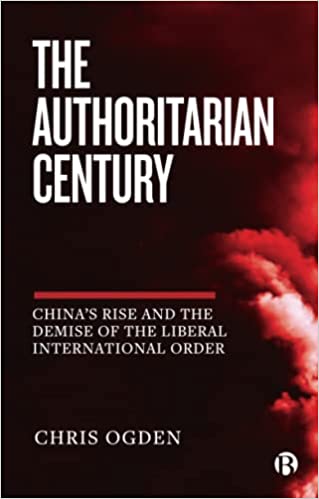

Dr Chris Ogden is a Senior Lecturer in International Relations at University of St Andrews and the author of The Authoritarian Century: China’s rise and the Demise of the Liberal International Order. Chris joined St Andrews in 2010 and his research analyses the relationship between national identity, security and domestic politics in South Asia (primarily India) and East Asia (primarily China) as well as the rise of great powers, authoritarianism in global politics, and Chinas coming world order. He has previously taught at the Universities of Edinburgh, Glasgow, and Durham and the Chinese University of Hong Kong. In 2018, Chris founded the European Scholars of South Asian International Relations (ESSAIR) Research Network. In an interview with Asian Lite’s Abhish K. Bose, he discusses the future of India – China relations and challenges

ABHISH K. BOSE: The Belt and Road project in which China is investing trillions of dollars in infrastructure projects around the Indian Ocean region is said to be aimed at encircling India and exerting influence across the globe including the military base it has established at Djibouti. This is posing a threat to India. What are the strategic benefits China aims through these initiatives and its security ramifications for India?

CHRIS OGDEN: The main benefits of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) are economic in that it seeks to enhance cooperation between China and other states (as well as between these states independently of China). Huge infrastructure projects and vast amounts of investment underpin the BRI, which is facilitated by China’s world leading economic prowess. There is also evidence that China is making many of its loans dependent upon recipient states recognising its “One China” policy, which is done to prevent criticism of Beijing’s policy towards Taiwan, Xinjiang and any internal Chinese matters, and which is acting as a set of restricting conditionalities for these states.

The implications for India are that these actions pull these states towards China and make them dependent upon Beijing’s economic success, which New Delhi cannot currently emulate, and which will reduce India’s regional influence and diplomatic impact. The financial aid given by China to longstanding strategic partner Pakistan as part of the BRI is a prime example here, as it does not consist of direct aid but of loans and credits increasing Pakistan’s debts to China. Just as China has done with Sri Lanka – whereby the financial aid given by China to Sri Lanka was not paid back by Colombo and as a result, China then acquired Sri Lanka’s biggest port of Hambantota on a 99 years lease – the same thing could happen with Islamabad and other states, which will reinforce China’s relative power and influence across the region.

Such actions will only serve to diminish India’s standing, as well as its ability to effectively resolve longstanding disputes with Pakistan and others, especially via economic means. In view of the current Chinese strategy that is designed to influence India’s neighbours via large amounts of financial aid, India’s best approach is to find ways in which it can work with South Asian states towards resolving shared threats. These concerns range from nuclear proliferation to transnational terrorism and the threat of asymmetric warfare. These could also be diplomatic efforts to confront other shared challenges such as environmental degradation, the smuggling of people, drugs and weapons across the region, and creating incentives for better intra-trading and economic self-reliance. As noted already, trying to outdo Beijing financially is not currently an option for New Delhi, but this may change.

ABHISH K. BOSE: What will be the future of the bilateral relations of India with China, especially in the context of the booming trade in between the two countries? India is depending extensively on China for various commodities and China’s exports to India are accelerating. What will be the future of this cooperation in the context of the disputes between the two countries?

CHRIS OGDEN: Notably both India and China share a series of challenges that underpin their growing economic links, and shared development/modernisation goals. Both face a myriad of internal issues which have the conceivable possibility to disrupt they’re becoming great powers. Some of these issues relate to China and India’s capability to maintain current rates of economic growth, and critically rest upon safeguarding a solid (and continuous) supply of energy and raw materials. Here oil and natural gas are the key components for continued economic growth. Other domestic challenges critically underline China and India’s rapid industrialisation, with both sharing more common challenges concerning high rates of inequality, corruption, and poverty, as well as the financing of huge, national new employment and social services provisions. The material gains of high economic growth thus have to be balanced against their often-destructive societal consequences.

Moreover, both China and India resolutely believe in an inclusive multi-polar world (whereby there are multiple poles of influence and power) – a belief that informs a worldview that is anti-hegemonistic. Such poles are typically China and India plus the US, Russia and the EU. In turn, India and China share key strategic outlooks concerning non-intervention, and strict anti-imperial and anti-colonial views (courtesy of their own historical experiences/exploitation by primarily western states which led to their mutual descent down the global hierarchy 200 years ago). Other shared beliefs regarding international peace and security; progress (i.e. development/modernisation); self-reliance and a desire for a more equitable/representative world, also substantially challenge most western-derived viewpoints concerning what constitutes the prevailing global order.

The hope would be that all of these shared linkages and shared challenges – within the context of an emergent Asian Century – will mitigate and balance out against the risk of further border confrontations. If Modi and Xi can see the bigger picture, as well as the destabilising threat that conflict between them would bring, then brighter relations between them can prevail. The hope here will also be that Xi can receive well-rounded advice as China’s leader, although his promotion of close associates at the recent 20th Party Congress may mitigate a truly balanced foreign policy, making it more open to Xi’s whims and nationalistic pressures. A possible economic downturn in China may also precipitate an external conflict as a way for the CCP to regain legitimacy from their various domestic constituencies.

ABHISH K. BOSE: Is India on the verge of abandoning its long-standing commitment to non-alignment and moving closer to the US? How far do you think that this change has been manifested and what role has China exerted in India to make this happen?

CHRIS OGDEN: I do not think that India will explicitly renounce non-alignment but it is clear that India is firmly tilting towards the US, especially concerning its policy towards China and the wider Indo-Pacific. In many ways, this is a good example of New Delhi’s high degree of strategic flexibility – where it can gain the best from a range of active relationships, even if they are counter-intuitive (such as India’s still close ties with Moscow). In the context of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, New Delhi’s diversification of its bilateral relations can help it to be less reliant upon Russian weapons, which will now come with a diplomatic cost in that they will explicitly associate India with Moscow. If India can have more weapons imported from other states – such as Israel or France or the US – it will also reduce this reliance and perceptual linkage.

China’s rise – and rising threat perceptions in India – have helped explain this shift but so have India’s own great power ambitions, and the desire internally to boost India’s status in whichever ways possible. The ongoing territorial tensions between India and China also played into this dynamic. Added to this, is that India wishes to remain as multi-aligned as possible, especially after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and mounting threat perceptions that China may soon invade Taiwan. Closer US and Western links thus give New Delhi ongoing strategic freedom, despite these negative events and potentially negative portents. They are also indicative of a much more multi-polar era in International Relations, which is a future that India supports and wishes to be a major part of as a recognised and influential twenty-first-century great power.